|

Earlier this summer, I became another victim of Lyme disease in the Hudson Valley. Shocking, I know. It's pretty amazing I've made it 31 years before finally succumbing to one of those nasty little ticks considering how much time I spend outside and in the Shawangunk Mountains. Thank goodness I had a successful and relatively uneventful course of treatment with antibiotics. When it was confirmed I had Lyme, I was ticked off to say the least so when talking with friends and family, I was telling them that Lyme got stuck with me, not that I got stuck with Lyme. It was a simple shift of my mindset but I was determined to beat the you-know-what out of that stupid tick and its "gift" to me. It messed with the wrong human!  But it also got me thinking about how people and clients I have worked with tackle injuries, pain and physical limitations. More often than not, I have a very good idea of who will do well with physical therapy and who might not be as successful before I even start treatment. Although they are contributing factors, it usually isn't age, gender, fitness level or severity of injury that predicts success. It is a positive mindset and "what do I have to do to beat this?" attitude that makes a huge difference versus a "why did this happen to me?" attitude. I realize I am speaking in generalities and there are always exceptions to the rule but time and time again those that jump head on into whatever challenge they face and are motivated to do whatever it takes to get better usually do. I am reminded of one of my favorite clients from a few years ago. At the time, she was 70 years old and had fallen resulting in ligament tears on both sides of her right elbow. It is bad enough when you tear one a la Tommy John, let alone two! One major surgery later to repair the ligament damage and she was scheduled for her physical therapy evaluation with me. Right off the bat I had a good feeling about her because "she didn't have time to be slowed down" by this. She wanted to get to work and I got lucky because she made my job very easy. Given her age, severity of injury and tissue quality, it would not be unreasonable to think she might end up with some limitations after such a major injury and surgery but again "she didn't have time for that". Couple that attitude with a great sense of humor and she beat all expectations and then some. I am convinced that her success was largely due to her positive mindset and less about my skill as her physical therapist. So my question is when pain, injury and physical limitation shows up for whatever reason, who got stuck with who? I prefer to think that it got stuck with me and picked the wrong human to mess with. I encourage you to think the same. Knowledge = Power; Share the Power:

0 Comments

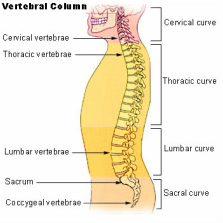

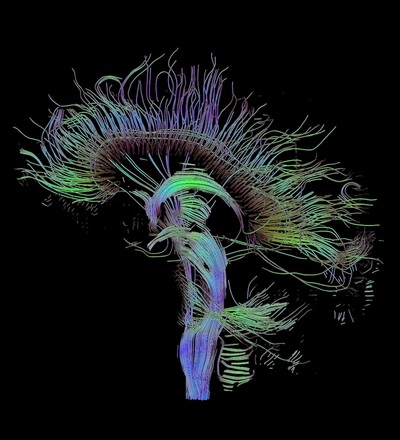

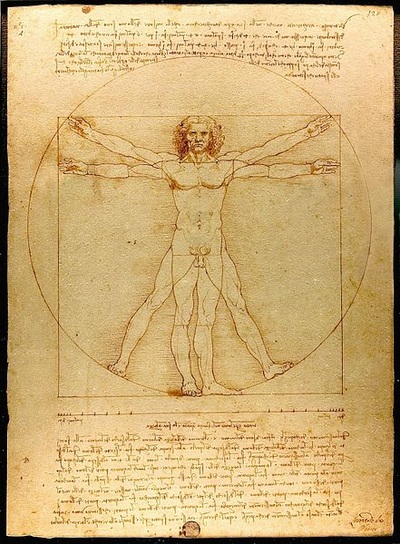

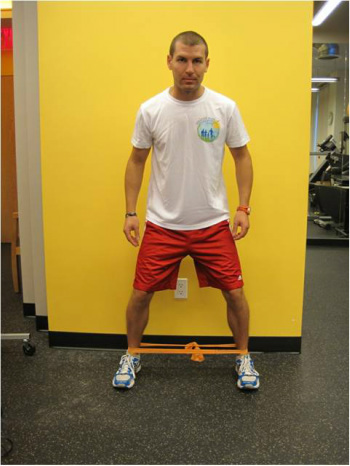

-Train Smarter, Not Harder-  I would rather not admit how many times I have violated this principle but let's just say too many. I am at a crossroads again which inspired me to put pen to paper (or fingertips to keys) in hopes that someone can learn from my mistakes. For me, it all began a couple of weeks ago. Up until then I was in the best running condition at this time of year for the first time in a while. I had and still have high hopes for this season of racing but I've recently developed consistent lower shin pain seemingly out of nowhere. There have been no drastic changes in my training routines that would explain an injury such as this. It was also alarming to be fine one day and then experience consistent pain during the next run without an event to point to as the culprit. Now it should be noted the pain I was dealing with was not severe in any way but having a consistent sensation of pain and discomfort on every step was concerning. I have finally learned that it would be better to pay attention to my situation now instead of putting it off or ignoring it like I've done before. That's lesson #1 if you are keeping track: Take care of things early on instead of ignoring them or allowing things to fester and get worse. Having dealt with other injuries in the past I have also learned that continuing to run probably wasn't going to help the situation. Chances are it was only going to make things worse so as difficult as it was I decided to shut things down until I could resolve this particular issue. That's lesson #2: Sometimes you just need to stop as much as you don't want to. Even if there is a race or event coming up, it's better to give your body a chance to heal, recover and figure out the problem instead of just pushing through. I am not an elite athlete and I'm guessing anyone reading this isn't either so it is unlikely there is anything truly on the line that is worth risking further injury and delaying a return to your desired activity. As frustrating as it is, having the patience to take time off from running (even with a couple of events in the next month) and get to the root of the problem will pay dividends for the rest of my season and if all goes well, for the long term too. That's lesson #3: Be patient. Life is much better when you can live to fight another day rather than push through and be sidelined for much longer. Being "tough" and training harder ends up backfiring more often than not. Thank goodness I have the skills to figure things out and treat myself in most cases. Having finally learned these lessons the hard way, I should be able to solve my particular injury in the short term so that I am ready for the rest of the season. There is a time and place to train hard(er) and this is not that time. I am finally allowing my brain to help me train smarter which will help me get back on the trails and racing as soon as possible. So I encourage you to learn from my mistakes when training for whatever your endeavor may be. When healthy and especially when dealing with injury, take full advantage of those three pounds of tissue between your ears and train smarter, not harder. Knowledge = Power; Share the Power: After graduating from my physical therapy program I took it for granted that the general public truly knows what physical therapy is. I assumed (first mistake!) most people knew the basics since it is a common and relatively mainstream intervention for injuries...or so I thought. It also seems like most people have sought care from a physical therapist or know someone that has and yet there still seems to be a lot of misinformation out there. Now that I've worked with hundreds of clients and have been talking to many people within my community as I build my practice I have found that there is a huge spectrum of knowledge about what physical therapy is and who it can help as it relates to an outpatient style clinic. Here are some of my favorite thoughts I've heard over the past several years about physical therapy: You only work with people after they've had surgery. It's just a bunch of exercises. Chiropractors take care of the spine, you do everything else. You use cool gadgets like ultrasound and electrical stimulation. I thought physical therapy is hot/cold packs, massage and a couple of exercises. It's kind of like personal training, right? This is PT? This is a lot different than I expected! While there is some truth to a few of these statements, they are pretty amusing if you ask me because there is so much more to physical therapy than these ideas. I especially like the last one. The most common definition(s) you will see for physical therapists is something along the lines of someone who is licensed to evaluate, treat and/or prevent pain, disability, injury, movement dysfunction, disease and functional limitations using physical, mechanical or chemical means including but not limited to therapeutic exercises, mobilizations and/or manipulations, and modalities (cold/hot packs, ultrasound, electrical stimulation, etc.). The definition I prefer to use is physical therapists are neuromusculoskeletal experts (not to be mistaken with gurus), movement educators and performance enhancers (the legal kind). This means we are specialists in the human body, how it moves and how to address issues like pain, injury, strength deficits, dysfunction, disease progression and performance optimization among many others. No matter what exact definition you use for physical therapy they are very open ended which is great because it means we can work with virtually anyone. Through our training we have the knowledge to analyze and understand each component of the neuromusculoskeletal system including the brain, spinal cord, nerves, muscles, bones, joints, tendons, ligaments and connective tissues. More importantly, we understand how each of these components interacts with each other to influence and allow the human body to function. In order to address any and all of these components and their impact on the whole system, we have an extremely diverse skill set at our disposal. To begin with, we perform a thorough physical examination and assessment as it relates to a client's specific situation and complaints. We have a wide variety of tests and measures that reveal valuable information which is interpreted to develop a diagnosis, a treatment plan and a prognosis. As far as treatment is concerned there are several interventions we can choose from in our skill set. The specific mix of interventions will vary from clinician to clinician and from client to client depending on each individual case. They include: Education: This is quite possibly the most important part of treatment. First and foremost, it is our job to listen so that we know what to teach and explain. It is our job to teach anatomy and physiology, pain science, biomechanics, relaxation techniques...whatever is necessary to help our clients understand their bodies better. It is our job to dispel myths and fears so that the brain and body isn't in a constant state of stress and exacerbating any issues. It is our job to develop a plan and strategies for our clients so that they are able to help themselves and reach their goals. Manual Therapy: More often than not, physical therapists will be using their hands at some point. It is here that you will see many different philosophies and schools of thought. It is impossible to list all of the manual therapy variations but some of the general categories they would fall under are soft tissue mobilization like trigger point therapy, various styles of massage, active release technique and instrument assisted soft tissue mobilization to name a few, nerve mobilizations, joint mobilizations including chiropractic/thrust manipulations (depending on the state; legal in NY), stretching, and facilitation of movement to retrain motor control and movement quality. How each of these is performed and accomplished will differ from clinician to clinician. Exercise: This can be broken up into two subgroups even though they overlap quite a bit. The first being neuromuscular re-education which is a fancy way of saying movement retraining. Think balance, control, reaction and technique. Single leg balance is a perfect example of an exercise that would be considered neuromuscular re-education. The second group is therapeutic exercises and functional activities. Traditionally you can think of strength training, flexibility and range of motion exercises fitting into this category as well as activities of daily living like walking, stair climbing and carrying objects. You would obviously need good technique and control in order to accomplish these more traditional types of tasks. With any of these exercises, what sets physical therapy apart is they are prescribed and progressed very specifically to achieve certain goals that can be tested and measured. It is much different than a general fitness plan. Modalities: This is where the gadgets can be listed like electrical stimulation (my favorite), ultrasound and mechanical traction. It would also include things like heat and cold therapy. In many cases, these passive modalities are used for pain control which is very helpful and a good adjunct to treatment but they will rarely ever resolve the underlying issues. That is what the education, manual therapy and exercise is for. There are other times when modalities are used therapeutically like electrical stimulation to improve activation (and strength) of the quadriceps after knee surgery or cold therapy to reduce swelling and inflammation. Long story short, physical therapy is an extremely versatile and comprehensive solution to issues related to the neuromusculoskeletal system. You might even consider physical therapists to be jacks of all trades as we have a wide array of skills to choose from in order to help our clients reach their goals. So if you have neck or back pain, we can take care of you. If you just had surgery, come on in. If you feel like you have balance issues, we've got that covered. If you can't play your favorite sport, we would love to fix that. If you have pain/chronic pain and you can't figure out why, we'll figure out why. I could keep going. As you can see, physical therapy is an excellent first option if you have pain, suffered an injury, have functional limitations, etc. and you want to resolve these issues so that you can move better, feel better and live better. Knowledge = Power; Share the Power: This is a follow up to my previous post Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome: What Is It? For the purposes of keeping this discussion on the shorter side I am going to skip the smaller subgroup of people who fall into the category of actual structural factors like a shallow patellar groove or bony abnormalities and focus on the majority of people who have functional deficits that can change with treatment. In most cases, the knee joint itself is usually healthy and absent any major issues but is sensitive and irritated as a result of deficits elsewhere. Upon examination, these deficits most commonly show up in the hip and/or the ankle. There are occasions where the lumbopelvic complex can play a significant role as well but not as frequently. For these reasons alone it is highly recommended to consult with a physical therapist who will perform a thorough physical exam to decipher which factors are the probable culprits causing the patellofemoral pain. Going back to 1976, Nicholas et al shed some light on this issue and found that proximal thigh muscle weakness was strongly associated with a variety of lower extremity conditions, particularly with patellofemoral pain. (1) More recently, Peters and Tyson performed a systematic review of the literature addressing proximal (read: hip) interventions and their effectiveness in resolving patellofemoral pain. Based on their review, there is very good evidence suggesting that proximal exercises is an appropriate and effective treatment, especially early on. (2) If you are wondering why this is the case, think of the hip as the foundation of your leg. Weak foundations of any structure leads to all kinds of problems and the same can be said of the hip. By strengthening the muscles of the hip and thigh you provide a solid foundation for the joints below, particularly the knee, to function as they were designed to. Another way to say that is strong hip and thigh muscles are able to control the mechanics of the knee more appropriately which can eliminate whatever was irritating the patellofemoral joint. Another driving factor can be below the knee at the ankle joint. The foot can as well but that's another topic for another day. To illustrate my point I've attached a video courtesy of Chris Johnson: As you can see, mobility and range of motion issues at the ankle can have a dramatic effect on knee positioning and mechanics. Imagine if that is what your knee is doing every time you squat, negotiate stairs or get out of your car. My knee(s) (patellofemoral joint) would be pretty cranky too! Last time I checked, the knee is supposed to flex forward and back more than rotate in. It doesn't take a rocket scientist to realize that this situation would completely change the forces and stresses applied through the patellofemoral joint potentially resulting in knee pain. Since I did not work with this individual it is unclear whether the ankle range of motion limitation is due to a loss of joint mobility, calf tightness or both. Again, this is why it is highly recommended to consult with a physical therapist who can figure out the main factors. Either way, by addressing the ankle through mobilizations and/or flexibility work, there is a high probability of resolving issues further up the chain like patellofemoral pain. At this point you might be saying "well that's great information but what can I actually do about it, Greg?" The following is by no means an exhaustive program but a good starting point for patellofemoral pain: Hip (Proximal) Strength

Ankle Mobility There are many good techniques to improve ankle dorsiflexion but this is my go to for two reasons: 1) It works, and 2) You don't necessarily need the compression wrap for it to be effective. For some other ideas and if you have access to wraps or bands, Mike Reinold put together a bunch of them in his aptly titled article Ankle Mobility Exercises To Improve Dorsiflexion. Calf Flexibility Calf Stretch Steps and stairs make for great calf stretching. In either case, your forefoot is placed on the edge with a slight toe in of about 5 degrees. If your heel is touching the floor, keep your leg straight and lean forward until you feel a strong stretch. If you are using a stair, allow your heel to drop until the same strong stretch is felt. Hold for 60-90 seconds and repeat 3-5 times. If you've been experiencing anterior knee pain or have even been diagnosed with Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome, these exercises may provide with some relief but consider consulting with a physical therapist who can fine tune your treatment. References: 1. James A. Nicholas, M.D., Alan Marc Strizak, M.D., George Veras, M.B.A., M.P.A. A study of thigh muscle weakness in different pathological states of the lower extremity. American Journal of Sports Medicine. December 1976, vol. 4, no. 6, 241-248. 2. JS Peters, NL Tyson. Proximal exercises are effective in treating patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2013 Oct; 8(5): 689-700. Knowledge = Power; Share the Power:  Recently, I've been asked a few times about Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS) as well as a few clients walk into my office with complaints of knee pain so I thought I'd put together some information to try to clarify some of the issues related to this common ailment. A quick Google search of 'Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome' provides you with almost 350,000 results and after this post, you'll be able to add another one to that list. Try many of the other iterations like PFPS, patellofemoral pain, patellofemoral syndrome, runner's knee, chondromalacia patella, movie-goers knee, etc. and you'll come up with thousands more. So what does this all mean? Well it means there is a ton of information (and misinformation) about one of, if not, the most common knee injuries to plague athletes, weekend warriors, office workers, young, old...just about anyone. The first goal is to define what it is. The simple version is pain around and/or behind the kneecap (patella) as it articulates or touches the femur. That sounds pretty straightforward but it can present itself in a variety of ways which is why you will find so many definitions/results with a Google search and among healthcare practitioners. It is also part of the reason why it has been given the vague designation of a 'syndrome'. The truth of the matter is nobody knows exactly what causes it or what is happening at the patellofemoral joint when PFPS shows up to the party. All we know is that the end result is pain. Since there is no consensus on what is actually happening, that makes finding a solution more challenging than say a broken bone or muscle strain. Add other knee injuries that can be confused with PFPS like iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS, yet another syndrome and another post), patellar tendonitis and bursitis and one can see how a 'simple' definition can become a complicated issue to diagnose and resolve. Though quite varied from person to person, there are some hallmark symptoms, however, that can help narrow down the differential diagnosis. These commonly include, but are not limited to, pain with squatting, ascending/descending stairs, running and prolonged sitting. Sometimes joint effusion or swelling will be present but again, this is quite variable also. Granted, these are common complaints among other knee injuries as well so PFPS often becomes a diagnosis of exclusion due to signs, tests and subjective complaints that can help distinguish between issues like meniscus pathology, tendonitis, bursitis, ITBS, etc. Now this is where physical therapists make the 'big bucks' (I can dream, right?). It is nice to have someone walk into my office with cookie cutter complaints so that the solution is easy but honestly, that situation doesn't happen very often. Instead, I am able to use my training and knowledge in anatomy, kinesiology and biomechanics, muscle physiology, neuroscience and psychology to assess the incredibly dynamic system that is the human body and brain to formulate a conclusion as to why someone is experiencing pain, in this case patellofemoral pain. Through careful observation, specific tests and measures, and most importantly, listening to my clients, I can deduce the driving factors of someone's patellofemoral pain and customize a plan to resolve his/her pain and limitations. Quite often, there are multiple factors involved and it is my job to determine the best way to address them and sequence the plan to get my clients back to moving better, feeling better and living better. Stay tuned for my next post to learn about some of the ways patellofemoral pain syndrome can be resolved. Knowledge = Power; Share the Power: What do you listen to when you run? Are you singing along to your favorite '80s mix, rocking out to Metallica's greatest hits or catching up on your favorite podcast? All of these actually sound like pretty good options but do you ever take your earbuds out and just listen to yourself run? There are a variety of ways to analyze running performance but using your auditory organs isn't commonly on that list. And unlike some of the others like video analysis or a biomechanics evaluation, you can perform an auditory analysis on your own and on any surface inside or out. Sound is a powerful tool and is something I use often with my clients and certainly for myself when I am running.

For the purposes of this discussion, the assumption is that there are no significant asymmetries (structural or functional) or previous injury, prosthesis or orthosis that prevents symmetry of the body in stance or with movement. The first, and probably easiest thing, you can key in on is the sound of your cadence. You should sound like a metronome when your feet hit the ground. There should be equal time (or silence) between each foot strike as well as equal time (or sound) when each foot is in contact with the ground. The latter can be a little more difficult to discern because the transition over the foot is generally quite quick. If there is a difference between foot strikes, then that may suggest possible issues like inefficiencies in your running mechanics or imbalances in higher joints which could lead to nagging injuries or limit your mileage or pace. Without overhauling your technique see if you are able to tweak your cadence first so that it is more even the next time you run. Assuming that your cadence is symmetrical, the next sound(s) to listen to may be a little more challenging: how your feet actually strike the ground. Are you a heavy hitter with a solid impact each time or are you light like a gazelle? Is one foot heavy and the other light? Depending on how light or heavy you land (and also which source you read), you are landing with 1.5 to 3 times your body weight on a flat surface. That is a lot of energy and it has to go somewhere. The Earth is certainly not going to budge which means all of that energy is translated into your body. If you land on the heavy side, injuries could pop up generally more structural in nature like stress syndromes and stress fractures. If you land exceptionally light or soft, this could actually mean that you're absorbing so much energy that you lose some efficiency in your technique and soft tissue injuries like tendonitis is more likely to show up. For instance you may bounce up and down more with each step rather than using that energy to move forward. There's a delicate balance between landing too hard or too light and listening to your foot strike can help you find that sweet spot. If you're lucky, you've got it already. Another sound to listen for is the foot slap. For those unfamiliar it almost sounds like two impacts when you land: first with the heel followed quickly by a loud "slap" by the forefoot. This is not to be confused with regular heel striking with a smooth transition versus other styles of landing. (That is a completely different discussion which will be covered in future posts.) This pattern generally describes someone who is over striding. When the foot and leg are too far out in front of your body and center of mass, it is difficult to transition smoothly and it is a less stable position which results in the distinct foot slap sound. The "easy" fix for this is to shorten your stride which may feel a bit awkward at first but long term will feel more smooth and comfortable when you run. Lastly, breathing. This encompasses all runners regardless of your cadence or foot strike patterns. Without getting into any specific technique (there are several out there but this is also a different discussion for another day), the one thing that they all have in common is rhythm. Make sure your breathing is consistent and has a rhythm to it so that you are constantly getting the oxygen you need to perform. Should there be any noticeable differences that persist and you are unable to correct them yourself or you develop pain, consider consulting with a physical therapist knowledgeable in running injury and performance to review your technique and history. See you out on the trails! If you found this to be helpful, please share!  Sitting. It didn't take long before I remembered why I don't like sitting for prolonged periods of time. It is only recently that I have spent more time parked on my posterior between marketing, blogging, (I am currently standing for this one), and reviewing new research along with many other administrative items as owner of my practice. Prior to my leap as a business owner, I was on my feet and moving more during the day as a staff physical therapist in several different clinics. Sitting was something to be cherished when I had the chance. Now under normal circumstances when you are sitting for a while, that soreness sensation, generally in your lower back/sacroiliac region, is the brain and body's gentle way of telling you to MOVE! ANYWHERE! JUST MOVE! It's quite an ingenious alarm system because it works really well....as long as you listen to it. Unfortunately I failed to listen to that initial alarm system recently and that soreness turned into a more constant and very annoying pain to the point where any static position was uncomfortable. It was even a bit challenging to fall asleep and my sleep is not something to be messed with. However, the solution was still an easy one....all I had to do was start moving more. Walking, running, (even a 10 mile trail race), and changing positions all felt great so it is no surprise that my constant pain has decreased almost back to its baseline of normal soreness if I sit for too long.  With this experience in mind, I wanted to share some issues related to sitting beginning with a basic understanding of the biomechanics involved and soft tissue considerations. There are different classifications of sitting but for the purpose of this discussion, I will focus on the very technical version that we all succumb to at some point during the day with or without knowing it: the slumped sitting position.  Before going any further, it is important to have a reference point, which would be standing in this case. In stance, the spine is naturally curved when looking at it from the side. More specifically, the lumbar spine, roughly the bottom third of the spine, has a lordotic curve which changes when we sit. Using the L1 vertebrae to the top of the sacrum, Lord et al measured the average decrease in lumbar lordosis angle from standing to an upright sitting position, (90 degree angle at the hips and knees). It was 49 degrees in stance and decreased to 34 degrees in sitting. (1) When the body gets lazy, gives in to gravity and slumps, this change is even more dramatic further decreasing the lordosis and sometimes eliminating it altogether. This by itself is not a cause for concern as it happens normally with many activities like putting your socks on or bending over to tie your shoes.  Something else also happens as a result of this position: stretching of posterior structures and tissues of the lumbosacral region. These can include muscles, tendons, ligaments, fascia, etc. In order to accommodate the decrease in lordosis, tissues must lengthen and stretch compared to their length in stance, which is a more neutral position for the spine and pelvis. It should be noted that this by itself is also not a cause for concern because tissues are stretched all of the time throughout the body as we move during the day. Time, on the other hand, is the enemy. When tissues are stretched, they trigger mechanoreceptors which are responding to the mechanical deformation of being lengthened. Initially the messages sent from the mechanoreceptors to the brain are not enough to trigger any type of soreness or pain response but the longer the time being stretched, slumped sitting in this case, the more frequent and "louder" those messages become. If it is long enough without a change, the brain processes the increasing messages and begins to perceive this as a potentially "dangerous" or "threatening" situation, and the output is sensations of soreness first followed by pain. This is the ingenious alarm system mentioned above as the expectation is that you will move so those tissues are not being stretched, (or not in "danger"), anymore allowing the mechanoreceptors, (and your brain), to chill out. This can obviously be overridden, as I did for too long and over several days, since most of the time you know that you are not actually in any danger, just uncomfortable. As I described above, any kind of movement, especially if you get on your feet for a bit to return the normal lordotic curve to your lumbar spine, usually relieves this type of soreness and discomfort. Unfortunately, many of us are stuck sitting, often slumping, for prolonged periods of time for work or in that super soft sofa you love. So do the easy thing: listen to that alarm system, get up and move a little bit. Your body, (and brain), will thank you for it. Stay tuned for Part II as I discuss some of the metabolic issues associated with prolonged sitting. References: 1. MJ Lord, JM Small, JM Dinsay, RG. Watkins. Lumbar lordosis. Effects of sitting and standing. Spine, 22 (1997), pp. 2571–2574. If you found this post to be helpful, please share! If you are looking for information about:

Without further ado, I'll start off with one of my favorite videos about pain. In short, pain is an extremely complex process involving countless factors like tissue damage (or lack of), stress, diet and sleep but is ultimately an output of the brain. That's right, the brain rules supreme and acts like a CEO deciding when you are in pain, how long you are in pain, what kind of pain, etc. So take the next 5 minutes to enjoy this short video which is a good introduction to understanding pain. |

Dr. Greg Cecere

Your personal physical therapist, movement educator and knowledge dispenser. Newsletter Sign Up

Enter your name and email to get Momentum PT's Movement Manual delivered straight to your inbox! It's your free monthly newsletter and guide to moving better, feeling better and living better! Archives

April 2017

Categories

All

Disclaimer:

The contents of this blog is meant for educational purposes only. Momentum Physical Therapy of New Paltz and Dr. Greg Cecere are not responsible for any harm or injury that may occur due to any information on this blog as it is by no means a substitute for a thorough evaluation by a medical professional. |

|

Momentum Physical Therapy of New Paltz, PLLC. Copyright © 2013-2024. All Rights Reserved.

Disclaimer: The contents of this site is meant for educational purposes only and utilization of any of the material is a personal choice. Momentum Physical Therapy of New Paltz and Dr. Greg Cecere are not responsible for any harm or injury that may occur due to those choices. This site is by no means a substitute for a thorough evaluation and guidance by a licensed medical professional.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed